Abstract

The study investigates the speech practices of rural Pothohari speakers in the home domain in the light of demographic variables: income, age, education and occupation. It discovers various social, economic, political and affective factors and their complex relationship with respect to language preferences and changes in patterns of use. The data for the study comes from recorded dinner time conversations of the native Pothohari speakers and their interviews. The study highlights interesting facts about family language use, language choices and the sociolinguistic situation of the Pthothari speech community. The findings suggest that Pothohari is undergoing the complex process of language shift and desertion. It is expected that the study will be a move toward raising awareness about endangering the subsistence of the indigenous language and will broaden the understanding regarding language maintenance and the shifting process.

Key Words

Language Attitude, Language Maintenance/Shift, Mother Tongue, Pothohari

Introduction

Indigenous languages are the invaluable heritage of a community. They enable the individuals of a community to communicate effectively and also play a key role in shaping their identities (Nishanthi, 2020). They are treasure houses of history, ancestry, culture and traditions of that particular group (Crystal, 2000). They are integral in affirming self-esteem and a sense of self-worth (Rahman, 2012).

Pakistan is a land rich in linguistic heritage, but unfortunately, this heritage is depleting due to the immense popularity and influence of dominant languages. Recently English and Urdu languages have become a standard of communication in our society, leaving no chance of resistance to adopting this standard due to economic and utilitarian benefits attached to it. This need of the time has sprouted an ever-increasing trend of deserting indigenous languages in favour of Urdu and English, which has put many of our native languages at the risk of extinction. This critical state of native languages anchors this study and engages in exploring the case of the Pothohari language.

Pothohari

Pothohari is the native tongue of the Pothohar plateau and some areas of Azad Jammu and Kashmir territory. It is a generations-old language and is being used as a home language in the region. It has 2.5 million speakers in Pakistan and almost 500000 speakers in the UK, making it the second largest mother language in the United Kingdom (Lothers & Lothers, 2010). In the census record of 2017, it is included in Punjabi totals making Punjabi the largest regional language spoken by 48% of the population (Zaidi, 2016). If the estimation is drawn on the basis of the native population, then Pakistani and AJK territories where Pothohari is spoken has a population of 8 million (Census record, 2017). So it can be safely estimated that it is the mother tongue of approximately 8 million speakers. The sheer number of Pothohari speakers reflects that the language has a strong position, but the sociolinguistic outlook of the language raises serious concerns. The worrying observations are that it is not officially recognized. It has oral tradition and does not exist in written form. It is not used for educational purposes. Its primary use is limited to informal use in the home domain, and that is also shrinking day by day. The especially educated class is displaying a negative attitude toward it and is adopting Urdu and English as home languages (Anjum & Shahid, 2012). This encroachment of dominant languages is taking place very rapidly, making the future of the vernacular uncertain.

Statement of the Problem

Indigenous languages are becoming endangered species due to the domination of powerful languages. In Pakistan, the overwhelming influence of English and Urdu languages has made this phenomenon acute. Dozens of our native languages are influenced by this linguistic domination and are facing the threat of extinction. Pothohari, a vernacular of the Pothohar region, is facing stagnation and rapid decline with respect to its utility and viability. The present study explores the changing trends in the use of Pothohari in the native speech community and its impact on the future of the language.

Research Questions

1. What are the language preferences and the usage pattern of native Pothohari speakers in the home domain?

2. What is the effect of age, occupation and education on the linguistic choices of Pothohari speakers?

3. What is the impact of English and Urdu on the linguistic practices of native Pothohari speakers?

4. What attitude does the Pothohari community hold towards Pothohari?

Theoretical Considerations

Language change or shift is an intricate phenomenon stimulated by various social, cultural, historical, economic and psychological factors. Karan (2008) proposed a basic taxonomy for language stability and shift, which includes certain motivational factors that deeply influence an individual's aptitudes in establishing linguistic choices (Reviewed in McEntee Atalianis, 2011). These include communicative, political, social identity, religious and economic factors. Fishman (1971) proposed cultural, social and psychological factors to examine the stability and change in language use (Cited in David, Ali & Baloch, 2017). These are all interlinked in their concert and exert accumulative pressure on determining linguistic choices. I believe these dynamic factors reflect the sociolinguistic situation in our country, especially in rural areas where our native languages were secure and enjoying worth and prestige quite a few years back. New communication technologies, education, modern media and transportation provided the rural community with the chance to seek influence from these factors to make a shift from vernacular to the dominant languages which the urban community was already experiencing. This article attempts to observe the changing trends of language use and shift in Pothohari rural community by utilizing these theoretical underpinnings.

Historio-Political and Cultural Aspects

In the historio-cultural backdrop of Pakistan, the traces of indigenous language desertion date back to colonial history when the colonizers deliberately imposed English at the administration level to consolidate their rule. They adopted the policy of pushing back the indigenous languages and promoted English as the language of the upper strata of society (Rahman, 2008). In the pre-partition era, the Persian language, which served as a powerful state language during the Mughal rule, was replaced by Urdu, which emerged as a military language through the Mughal army. Later, Urdu became an emblem of Muslim identity during the freedom fight in Pakistan. It became lingua franca, and after the establishment of Pakistan, it came to be recognized as the national language of Pakistan. In 1947, British rule ended, but their imperialistic penetrations continued in the form of English, serving as the country's official language. Out linguistic policies have always been inclined towards the promotion of dominant languages and did not pay attention to framing consolidated policy to maintain the worth and prestige of indigenous languages (Bakar, 2014). This situation is still ongoing, allowing no opportunity for indigenous language development.

Economic Aspect

From a Marxist angle, language is a commodity that bears economic worth. Dominant languages are associated with power and progress. (Baart, 2003). Naturally, the languages that are pragmatically competent have better chances of survival and development. In the incubation globalization era, the English language represents economic activity and promises financial security (Nawaz et al., 2012). It is the language of education, business, information technology, science, media, world politics and cyberspace. Knowledge of English is taken essentially to economic prosperity. Urdu is important in our context, next to English, occupying the country's national language status. It is the primary medium of instruction in state schools and is spoken widely across the country. It is considered the most civilized language of communication. Like English, it carries pragmatic value and is recognized as a symbol of economic success and social prestige. Rahman (2012) argues that our state policies, educational system and mass media are promoting them as dominant languages. This convergence of our economic and social forces has made Urdu and valuable English commodities making indigenous languages less competent. Pothohari is facing a similar fate, which is discouraging its users from maintaining it as their mother tongue.

Psychological Aspect

According to Yoshioka (2010), language maintenance or shift is by dint of the value assigned to the language by its speakers (p. 09). The assigned value is two-dimensional: the prestige aspect and the language usefulness. In the first case, the community recognizes it as an identity marker (Baart, 2003) and shows the desire to speak it. They feel pride in it. In the second case, the communicative use of the language determines its worth, and its speakers are convinced to retain its use on the basis of its functional value. Our unstable political history challenged the concept of language prestige (Rehman, 2008). It resulted in serious psychological consequences, which are responsible for our shift from vernacular to the dominant languages. The colonial rule established superior and inferior relationships between the colonizers and the colonized. The colonizer's regarded their culture and language as superior, while the local culture and languages were stigmatized as backwardness (Ali, 2015). This imperial influence is not allowing us to assign prestige and value to our indigenous languages and cultures today. In addition, the British invasion took place with the English language, which destroyed the utility of our native languages. This linguistic imposition was by force at that time, but the modern technological and scientific era has made it necessary.

Literature Review

The native language decline is happening at an alarming rate all over the world. A few economically and politically dominant languages are replacing thousands of the culture-rich native languages. Pakistan is no exception to it. The changing economic, political, and social circumstances and the influx of modern technological inventions have created an unfavourable atmosphere for the efficacy of the local languages. As a result, native speakers are discerning negative attitudes towards them (Lothers & Lothers, 2010, Asif, 2005, Riaz, 2011), and a large majority of our indigenous languages are losing their utility and worth very rapidly.

An enormous amount of literature is present on community language in the whole world. Many studies have been conducted to explore the status of indigenous language, the phenomenon of language maintenance and shift and the factors that cause language change in recent years. Ravindranath (2009) examined the social and linguistic factors causing language shift in the Garifuna community in Belize. The investigations revealed that the minority language was fighting a futile battle against the dominance of Belizean Creole. Balfaqeeh (2015), in her study, investigated a generation-based change in the lexicon of Emirati vernacular. Her findings revealed that globalization, modernity, and the extensive use of English in modern communication technologies have certainly impacted Arabic language communication in the Gulf region. Ortman and Stevens (2008) have studied inter and intra-generational language shifts of Spanish among Hispanic Americans. They exploited the classic model of the three-generation language shift. Their results showed that after the first generation of Hispanic immigrants, inter and intra-generational factors played a very important role in the disappearance of the Spanish mother tongue among the Hispanic community in an American context.

A number of studies are also available on Pakistani indigenous languages. Abbasi and Aftab (2019) conducted a case study on Dhatki-speaking urban youth. They used the sociolinguistic profile of thirty Dhatki-speaking undergraduate students to examine the language change and shift from the mother tongue to the other tongue. Their findings revealed that Dhatki speakers are shifting to Sindhi, Urdu and English languages to fulfil their economic, social and academic needs.

David, Ali and Baloch (2017) used Fishman’s domain concept to measure the extent of Sindhi language maintenance and shift. They came up with the findings that the Sindhi language is maintaining its cultural identity and use in vital domains of life. Asif (2005) investigated the phenomenon of Siraiki language maintenance and shift in Multan. Her findings suggested that Siraiki speakers are shifting from their ethnic language to officially promoted languages. The same conclusion is drawn by Riaz (2011) in her study about the desertion of the Punjabi language. If the number and investigated aspects of these studies are compared with the magnitude of native language erosion and decline, then these studies seem scarce. Here the present research emerges as a valuable contribution to the existing literature.

Research Methodology

Research Site and Sample Selection

The data is collected from district Rawalpindi. Pothohari is the mother tongue of this region. The sample consists of six native Pothohari-speaking rural families consisting of thirty-seven participants of different age groups with varied qualifications and occupations.

According to Palinkas et al. (2016), a predetermined criterion is essential to identify and select the participants. Economic standard is used as criteria to make the selection of participant families. Economic status has a direct impact on the living standard and social status of the people. It plays a key role in making language choices as rich people have access to modern and better educational and employment opportunities, so their language practices take shape accordingly. Average monthly income and expenditure measurements statistics (2018-19) published by the bureau of statistics, the government of Pakistan, are used to determine the economic status of the selected families. The revenue limit for poor-income families is marked as less than PKR 500000 per month, for middle-income families PKR 500000-100000, and for upper-income families PKR.100000 and above. Purposeful-random sampling technique is used. Sample families are shortlisted randomly to minimize the risk of biasedness. Purposive sampling is done for the selection of interviewees and those informants are preferred who were knowledgeable in my understanding and were expected to supply rich data.

Data Collection

Conversational recordings and interviews are used as tools of data collection. Recording of dinner time family conversations is preferred to ensure the presence of all the family members because usually, dinner is the collective meal of the families in rural areas. Two sessions are audio-recorded from each participating family. The collective duration of recordings is two hours and forty minutes. Twelve semi-structured interviews, two from each participating family, are conducted. The total duration of these interviews is four hours. During the whole process of data collection due ethical guidelines were observed and followed.

Analysis

The data was obtained in the form of recorded family

conversations and semi-structured interviews are analyzed separately. Recording speech is analyzed using quantitative, qualitative and descriptive approaches to investigate the speech practices and language choices of the informants. Thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews is conducted to get close insights into speakers' attitudes to their native tongue and factors that establish language choices.

Findings and Discussion on Recorded Speech

The tendency of Language Shift and Maintenance

Findings concerning the status of Pothohari use in the home domain are described and discussed according to various demographic variables like income group, age, education and occupation. The percentage is determined by the total number of informants. The distribution of language use on the basis of income is presented in the given figure.

Figure 1

The displayed facts provide evidence that Pothohari is in dominant use as a family language in poor and middle-income groups. Twenty-three out of thirty-seven participants belong to these two income groups. All of them acquired Pothohari as their mother tongue. The majority are bilingual with Urdu and Pothohari and prefer the use of their native tongue for family communication. It affirms their constancy to the native tongue. In the upper-income class, a tendency for language shift from Pothohari to Urdu is observed. Thirteen participants belong to this income category. 69% acquired Pothohari as their mother tongue, and among them, only 44% maintain its dominant use in family conversation. It is a common perception that people belonging to the poor income class are confined to their home-grown language and are least influenced by the dominant languages due to fewer opportunities for exposure to them. On the other hand, those belonging to high-income status have sophisticated language usage patterns and are keen on their preference for dominant languages. In the sample data, this variable is playing in a conventional manner. Low and middle-income groups are maintaining the use of Pothohari while the upper-income group is deserting its use. Because affluent class has access to better educational opportunities and modern amenities of life like internet, TV, computer and mobiles etc. which offer immense exposure to the powerful languages and are sure way to influence language choices of their users. Age-wise distribution of Pothohari use is given below.

Figure 2

It is found that the majority of the participants acquired Pothohari as their mother tongue. However, all of them are not maintaining their dominant use in the home domain. The age group 20-59 years has the highest population in the data. All participants from this age group acquired Pothohari as their first language, but only 88% of them maintained its use. The second highest age group of the data is nineteen years and less. Only 33 % of the participants from this age group have learnt Pothohari as their mother tongue, and 25% are retaining its use. The age group with less number of participants is sixty years and above. All these participants are retaining Pothohari as the dominant language of communication at home. The percentage values highlight a gradual and sequential decline in Pothohari use generation-wise. The older generation is maintaining the use of Pothohari. The 2nd generation, or young generation, owns Pothohari but is gradually moving away from its use. The 3rd generation is deserting it and shifting to Urdu and English languages.

Education is a key factor in establishing the language preferences of the speakers. The research participants are divided into three educational levels, as is reflected in the following table.

Figure 2

It is found that the majority of the participants acquired Pothohari as their mother tongue. However, all of them are not maintaining their dominant use in the home domain. The age group 20-59 years has the highest population in the data. All participants from this age group acquired Pothohari as their first language, but only 88% of them maintained its use. The second highest age group of the data is nineteen years and less. Only 33 % of the participants from this age group have learnt Pothohari as their mother tongue, and 25% are retaining its use. The age group with less number of participants is sixty years and above. All these participants are retaining Pothohari as the dominant language of communication at home. The percentage values highlight a gradual and sequential decline in Pothohari use generation-wise. The older generation is maintaining the use of Pothohari. The 2nd generation, or young generation, owns Pothohari but is gradually moving away from its use. The 3rd generation is deserting it and shifting to Urdu and English languages.

Education is a key factor in establishing the language preferences of the speakers. The research participants are divided into three educational levels, as is reflected in the following table.

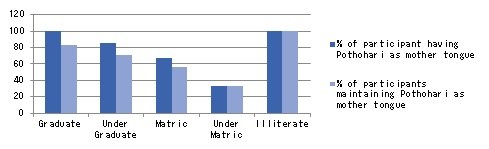

Figure 3

Distribution of Native Language use on the Basis of Education.

The tendency of language shift is present in all qualification categories except the matric and illiterate category. Of the participants who fall in the matric category, most of them have matric as the terminal qualification. In both matric and illiterate categories majority of the participants are aged and less qualified. They hold competency in their mother tongue and use it with ease and confidence. In the under matric category, the graph of native language acquisition and abandonment is running down sharply compared to the rest of the categories. In this category majority of the participants are young children and students whose language choices are largely moulded and influenced by their educational environment and the aspirations of their parents for a better future. In graduate and undergraduate categories, language shift is obvious but gradual at this point of time, which may be due to established competency in the native language. The observed facts signify that education is influencing the language choices of the rural speakers, and a gradual language shift has started to take place among the children group, which is a definite danger to the vitality of the Pothohari language.

Occupation or employability is strongly connected with the extension of social connections. So it is a strong variable in determining language choices. The occupations identified in the data and language usage percentages are displayed below.

Figure 4

: Distribution of Native Language Use on the Basis of Occupation.

In this category, the speakers influenced by language shifts are teachers, students, and housewives. 17% of teachers are not maintaining the use of Pothohari. They are influenced by dominant languages because they are part of an academic environment that accepts Urdu and English as operational languages. The language choice of housewives is highly influenced by Urdu. All of them acquired Pothohari as their mother tongue, but only 50% of them maintained its use. This influence is attributed to their extensive interaction with their children, who are picking Urdu and English due to educational needs and the social and electronic media that are using Urdu and English essentially. The dominant category that did not acquire Pothohari as their first language is of students. 31% have acquired it as 1st language, and 23% are maintaining its use. Students are the growing generation and the future of their families. They are highly influential individuals in society. They absorb influences from dominant languages due to their diversified communicative connections with family, friends, academic associates etc. and pass them on to others more easily and strongly. In this particular context, it is predicted that their shift from Pothohari to Urdu will have an adverse effect on its vitality on a large scale.

The least co-correlation between participants' occupation and their language choices exists for the rest of the categories. The reason for this obscurity is a small sample size. Sometimes there is only one participant in a particular occupational group. In such cases, it is difficult to compare and contrast the speech choices and differences. This insufficiency provides the direction to explore this variable with a large sample size in some further studies to authenticate the assumptions of this study.

Intergenerational Language Transmission

Transmission of language to the next generations is the basic yardstick to measure the vitality of any language. This practice is essential to the survival of languages. This feature is observed as very significant in investigating the status of Pothohari use because this language is not popularly in recorded form, and its survival is only through intergenerational transmission. The findings regarding the intergenerational transmission of Pothohari families are presented below.

Figure 5: Intergenerational Transmission of Pothohari.

67% of participating families are transmitting Pothohari as their native tongue to their young generation. Four participating families are seen as interested in maintaining their Pothohari identity through their mother tongue transmission to children. If these facts are estimated according to the UNESCO standard (2003) for language survival, then Pothohari is in a safe zone in rural areas for the time being. Two families from the upper-income group have demonstrated a changed behaviour. They do not prefer the children to learn and use the Pothohari language. This negative attitude to the native tongue reflects the parents' desire for their children to achieve success and economic prosperity through dominant and powerful languages. They are willing to secure their future at the expense of their mother tongue. In fact, our linguistic policies have never granted space to local languages to facilitate the users in getting material gains (Rahman, 2012). As a result, the function of most of our indigenous languages has become limited to informal conversation, and that is also declining with the passage of time. Overall the investigated statistics show a slight tendency of language shift from native tongue to national language in upper-class rural families, which predicts that Pothohari may lose its position of family language in the near future.

Influence of Bilingualism and Trilingualism

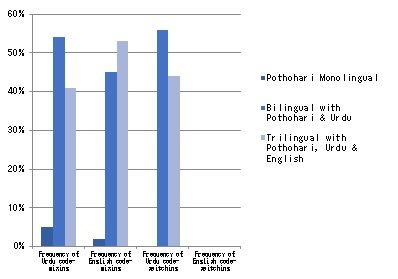

Another prominent aspect of the speech practices of the participants is the impact of Urdu and English on their native speech. This effect is observed in the form of code-mixing and code-switching. In the existing data, code-switching is perceived in terms of switching from one language to another in the same conversation on the basis of purpose or situation, while code mixing is perceived in terms of transferring linguistic elements from one language to another (Rasul, 2013). Such influences are due to the interaction of different codes. There are three types of speakers identified in the study sample: (1) Pothohari monolinguals who have competency and proficiency in the native tongue only. (2) Bilinguals with Pothohari and Urdu languages have competency and fluency in both these languages. (3) Trilinguals with Pothohari, Urdu and English languages. They are fluent speakers of Pothohari and Urdu languages but lack proficiency and competency in the English language. The comparative details of the observations with the language background of the participants are displayed in this graph.

Figure 6: Influence of Bilingualism and Trilingualism.

The frequency of code-mixing and code-switching is high in bilingual and trilingual speakers. Monolingual speakers of Pothohari are relatively maintaining its use with purity. There are several noteworthy observations about the use of code-mixing and code-switching in the data.

First to note is Code-mixing of both English and Urdu languages is present, but code-switching is taking place in the Urdu language only. English code-switching out numbers Urdu code-switching. It indicates that the speakers are influenced by the English language but lack functional competency in it. It is ascribed to the linguistic environment and exposure of the participants to Urdu and English languages.

Secondly, code-mixing is limited to lexical insertions. English and Urdu lexis are incorporated into native speech. The pattern and use of code-mixing vary among users on the basis of various demographical variables like age and educational and professional activity. The utterances of some participants are densely code-mixed compared to others. In a single exchange of speech, a number of Urdu and English words are incorporated by the speakers. In the majority of cases, such use is made by the educated participants. On the other hand, the speech of less educated participants is also no exception. Especially housewives who are not formally well educated in most cases and spend most of their time in the house doing home chores are also found influenced by this feature. They are in touch with media and take up influence from their children and other family members who are part of a wider social, educational and economic set-up that accepts Urdu and English as the only desired languages.

Thirdly, a wide variety in the choice of the lexicon is seen in the recorded conversations.

1. Firstly, there are certain words of foreign language/languages for which equivalents do not exist in our native languages and borrowed words are adopted to facilitate the communication. These include mobile, charger, cartoon, bank, pizza, youtube, tweet, college interview, etc.

2. Secondly, there are certain English and Urdu words whose use has become popular. They have been accepted as part of our native languages like the kitchen ( Basati), bartan( panday), koney (chooken), cup (kouli), spoon ( kashek), tasetey( swadli), time (weela) and doctor etc. Their equivalents exist in their native language, but their usage is not favourite. Ordinary people, irrespective of their knowledge of English and Urdu, understand them well. While their typical Pothohari equivalents have become outdated and have fallen out of use as they are not aligned to modern civilized talk and Urdu and English vocabularies are offering better alternates to them. Most of these lexical insertions have become permanent adaptations. Users take them for granted and do not feel the need to explore why and how they are in their constant use.

3. Thirdly, hybridization is observed in the recorded speech. Users have tried to adjust the words of a foreign language according to the rules of the native language. Word “plataen” (plates) is used in the sample data. The plate is an English singular noun which is changed to its plural by applying Urdu grammatical rule for the plurals. Similarly, the English word light is used with local pronunciation Laet, although its Pothohari equivalent Ba’ati exists. Such inflections exhibit the influence of languages on each other in a multilingual environment.

4. Fourthly, there is a factor of ease. Sometimes users adopt influences for the sake of ease of communication. Some contextual variations pose difficulty and motivate the speakers to make alternative choices. For example, in the present data, word bag is used. It is Pothohari equivalent carries various contextual variations. In Pothohari word Bag is used for ready-made bags. For school bags word basta is used and for a bag that is made of cloth, thela word is used. In such a situation, common terminology that fits all the situations is preferred and adopted by the speakers out of ease.

5. Fifthly, unnecessary use of English lexis is found in the data. Fake, change, green, start and Drosophila are used unnecessarily by the speakers just to show off knowledge and to add linguistic flavour and modern style to native communication patterns.

The findings report that the use of Pothohari in family communication is reduced by 33%. In low and middle-income families, its dominant use is safe to some extent. In the upper-income group, a language shift is observed. 46 % of participants of this class have replaced it with Urdu in the home domain. The majority of them are young children. They have access to better educational opportunities, and their parents prefer them to learn Urdu to be socially and economically successful. It has a profound impact on their language choices and usage pattern. The rest of the participants who have past the phase of career building are comfortable with the use of their mother tongue in the home domain.

Findings of Semi-structured Interviews

Trends in Language Use

The sample interviewees reported variant language usage patterns for family conversation.

1. Parent generation or the older family members usually use Pothohari when talking with each other. But they switch to Urdu when they talk to children. Informant no. 1 from family no. 6 reports, "mein aur mere husband apas mein aur ami abu key sath Pothohari me baat kerty han bachoun sey hum Urdu mein baat kertey han. (We both husband and wife talk with each other and with parents in Pothohari, while with children, we speak in Urdu). Almost all the interviewees shared the same pattern of language usage among family members. The recorded conversations also verify this usage pattern. For example, in family no. 5, daughter-in-law switches to Urdu in utterance no. 3 saying to her son utho udher ho phopho bi bethe gi (get a side, aunt will also sit there). Similarly, in utterance no. 78 mother makes a switch from Pothohari to Urdu, saying to her daughter natash ye bartan utha k kitchen me ly jao (Natasha takes these utensils to the kitchen).

2. Children use Urdu when talking among themselves. The eighteen-year-old interviewee from family no. 6 reports, "school mein hum Urdu istamal kertey han aur ghar mein be behen bhayon sey Urdu hi bolti han. Pothohari bi aati ha, Urdu mein guftugu sey lagta ha hum educated han" (we use Urdu in school as well as in home with siblings, talking in Urdu gives the impression that we are educated). In family no. 5 seventeen year old students tells, "hum gar me apas mein Urdu hi use kertey han, parents bi hamarey sath Urdu hi boltey han” (we speak Urdu in home among ourselves, our parents speak Urdu with us). These participants have displayed the same usage pattern in their dinner time conversations as they have expressed in their interview reporting.

3. Young members switch to Pothohari when talking to parents who cannot speak Urdu. Interviewee 2 in the family no six says, “hamari ami itni pari likhi nahi han tou un key sath hum Pothohari mein baat cheet kerty han” (Our mother is uneducated, so we talk with her in Pothohari). Interviewee no. 1 in family no.1 reports, “.hamaar mahool Pothohari ha, apney baroun key sath hum Pothohari boltey han, bachoun key sath hum school ki waja sey Urdu boltey han” (our environment is Pothohari, we speak Pothohari with our elder, with children we use Urdu due to their education). These expressions are perfectly compatible with the findings observed through recorded conversations of the families.

Lack of Official Patronage

During the interview sessions, the participants expressed that Pothohari has no official recognition. It is not used in education, media, offices and the job market. The literary activity in the language is scarce, and very little amount of literature is available in it. Time and again, the informants highlighted its inadequacy in practical life. Interviewee 2 in the family no 3 says, “ab modern dour ha Pothohari ka kisi jaga koi istamal nahi ha swaiey gar key, har jaga Urdu aur English istamal ho rahi haen” ( In modern times, Pothohari finds a place for use nowehere, everywhere English and Urdu are being used). In family no. 2, interviewee no. 1 says, “hum bachoun ko Urdu sikha rahey han kunkey wo agey school me ja key Urdu hi boolen gey” (We prefer children to learn Urdu because they have to speak Urdu in schools). It also comes to notice that nobody participating in the study reads any piece of literature in Pothohari. All participants agreed that literature in Pothohari is not easily available, and they never got an opportunity to read it. These insights expose that lack of official patronage is one of the main reasons for eliminating the value of the vernacular due to which native speakers are attracted to dominant languages.

Stereotyping and Negative Attitudes towards Pothohari

Crystal (2000) asserts that the attitude of a speech community towards its language plays a key role in language maintenance or shift. Positive attitudes promote language, and negative attitudes cause language shift. Language stereotyping is a major factor in the process of language shift. It refers to certain negative attitudes attached to a particular language. The interviewees of the research explicitly admitted that due to negative stereotypes associated with Pthohari, they do not prefer its use for themselves as well as for their children.

The status of Pothohari in comparison to English and Urdu is considered inferior both socially and economically. It is stigmatized as the language of villagers and uneducated people. There are many instances where the informants expressed that Pothohari is uncivilized and backward. A few are mentioned here. “Hamrey loug Pothohari bolney waley ko pendou smajtey han” (our people consider Pothohari speakers backwards) (interviewee no 2, family no. 2). "Hostel mein larkeyan kehti then ap Pothoharo boltey ho tou lagta ha laer rahey ho, is cheez neh hamein discourage keya” (In hostel girls used to say when you speak Pothohari it seems you are fighting. It discouraged us) (Interviewee 1, family 4).” Pothohari haarsh se language ha is mein baat kr key acha nahi lagta, uncivilized sa lagta ha” ( Pothoahri is a harsh language, do not feel good using it, it seems uncivilized) (Interviewee 1, family 5).

The low and stigmatized status of Pothohari is the biggest cause of feelings of rejection and inadequacy in relation to the maintenance of the language among the native speech community.

Economic and Academic Prospects and Language Choice

During the conversational analysis, a range of factors are spotlighted that are observed playing their role in determining the language patterns and choices of the participants. These include: education, media, popularity and official patronage of powerful languages, inadequacy of native language repertoire and status consciousness. Among these the interviewees have regarded economic and academic factors more influential. They are key aspects in giving functional value to a language and make sure its survival (Nishanthi, 2020). In this lieu informant 1 in family no. 4 has expressed: “apni zuban ka apna hi charm ha hum sirf bachoun ki education aur career kei waja sey Urdu ko prefer kertey han” (Our native language has its own charm, we just prefer Urdu for the sake of education and career of our children). “Taleem aur job security key ley hum in per dependent han” (We are dependent on these languages for education and job security) (Interviewee 2, family 5). Similar views are expressed by the rest of the research participants that the educational and economic needs of the time have made it compulsory to give priority to English and Urdu.

Future of Pothohari and the Perceptions of Native Speakers

Generally the research participants are not very optimistic concerning the future of their vernacular. All of them highlighted the fact that it is being replaced by Urdu rapidly in everyday communication. They expressed that they see no other place for its use except home or family and in coming years this informal use will get limited to old speakers and in next two-three generations it will also come to an end.

Informant no. 1 in family no.6 says, “Ab hum barey ya bohrey loug isko istamal kar rahey han, hamarey bachey isko nahi seekh rahy to anay wali dou teen generations mein yeh khatam ho jaey gi” (Now we old or adult people are using it, our children are not learning it, in next two to three generations it will come to an end.)

When asked how do you see and feel this language shift and the influence of dominant languages on the purity of Pothohari? The majority of them expressed a positive attitude towards this change. Interviewee 2 in the family no. 1 has expressed: "Mujey to acha lag raha ha kunkey jo advance system aa raha ha bachoun ko agay samajney mein asani rahey gi aur unein angreezi boulney mein koi diqat nahi ho gi” (I see it a good change because the system is getting advanced and the children will not feel difficulty in speaking English). "Aj kay dour mein koi bi zuban pure nahi rahi, her zuban key andar different languages key ilfaz istamal ho rahey han, mujey lagta ha jis tarah har chhez develop hoti ha istarah ye zuban mein be development ho rahi ha" (Now a day none of the languages is pure, all languages are using foreign words, I feel it is the development of language like the development of other things) (interviewee1, family 2). These expressions show the acceptance of language change and the alienated and indifferent attitude of the community towards their mother tongue.

Conclusion

The findings provide sound evidence to conclude that Pothohari is the language of everyday use in the home domain. Its use is maintained by the participants belonging to different age groups, educational backgrounds and occupations. In this respect, it is maintaining its position. At the same time, the study also illustrates that the process of Pothohari language transformation is at work in rural areas. The investigations accentuate the endangering vitality of the language as its transmission to the next generations is not taking place very effectively, and its use is becoming limited to the older generation. 67% of participating families are passing it as their mother tongue to their children. The majority of the parents wish their children to learn Urdu and English to secure a better future. Moreover, the recognition and influence of dominant languages like Urdu and English are infecting its purity as well as popularity. These observations forecast a rapid language shift and an uncertain and insecure future for the Pothohari language in rural areas in the near future.

Limitations and Recommendations

The study makes an invaluable entry in the existing literature available on indigenous languages by exploring the declining state of Pothohari. It takes input from a very small sample of native Pothohari-speaking families residing in rural areas, so the findings cannot be generalized to the entire Pothohari-speaking population. A similar study is required to analyze language practices, attitudes and status of mother tongue in urban areas. Further, based on the rural and urban sociolinguistic situation of Pothohari, a large-scale study is needed to carefully evaluate the status of the language in the native region.

References

- Abbasi, M., & Aftab, M. (2019). Mother tongue or the other tongue? The case of Dhatki-speaking urban youth. Balochistan Journal of Linguistics, 7, 81-92.

- Ali, S. (2015). Minority Language speakers’ journey from the Mother tongue to the other tongue: A case study. Kashmir Journal of Language Research, 18(3).

- Anjum, U and Siddiqui, A. (2012). Exploring Attitudinal Shift in Pothwari: A Study of the Three Generations. Pakistan Journal of History and Culture, 33(1).

- Baart, J. (2003). Sustainable development and the maintenance of Pakistan’s indigenous languages. Proceeding of conference on the state of the social sciences and humanities: current scenario and emerging trends Islamabad.

- Bakar, A. (2014). Culture Infiltration through Language: Impact on Contemporary Pakistan. M.Phil. University of Management and Technology, Lahore. http://escholar.umt.edu.

- Asif, S. (2005). Siraiki: A Sociolinguistic study of Language Desertion. Ph.D. University of Edinburgh.

- Balfaqeeh, M. (2015). Generational change and language in the UAE: The desertion of the Emirati vernacular. Globe: A Journal of Language, Culture and Communication, 1, 17- 30.

- Crystal, D. (2000). Language death. In Applied Psycholinguistics (269-273). Cambridge University Press.

- David, M., Ali, M., & Baloch, G. (2017). Language shift or maintenance: The case of the Sindhi language in Pakistan. Language Problems & Language Planning, 41(1), 26-42.

- Lothers, M., & Lothers, L. (2010). Pahari and Pothwari: A sociolinguistic survey. SIL.

- Rasul, S. (2013). Borrowing and Code Mixing in Pakistani Children’s Magazines: Practices and Functions. Pakistaniaat: A Journal of PakistanStudies, 5, (2).

- Ravindranath, M. (2009). Language Shift and the Speech Community: Sociolinguistic Change in a Garifuna Community in Belize. Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania.

Cite this article

-

APA : Tabassum, S., & Qadir, S. A. (2022). Changing Trends in Indigenous Language Use in Pakistani Rural Community. Global Social Sciences Review, VII(I), 264-278. https://doi.org/10.31703/gssr.2022(VII-I).26

-

CHICAGO : Tabassum, Samina, and Samina Amin Qadir. 2022. "Changing Trends in Indigenous Language Use in Pakistani Rural Community." Global Social Sciences Review, VII (I): 264-278 doi: 10.31703/gssr.2022(VII-I).26

-

HARVARD : TABASSUM, S. & QADIR, S. A. 2022. Changing Trends in Indigenous Language Use in Pakistani Rural Community. Global Social Sciences Review, VII, 264-278.

-

MHRA : Tabassum, Samina, and Samina Amin Qadir. 2022. "Changing Trends in Indigenous Language Use in Pakistani Rural Community." Global Social Sciences Review, VII: 264-278

-

MLA : Tabassum, Samina, and Samina Amin Qadir. "Changing Trends in Indigenous Language Use in Pakistani Rural Community." Global Social Sciences Review, VII.I (2022): 264-278 Print.

-

OXFORD : Tabassum, Samina and Qadir, Samina Amin (2022), "Changing Trends in Indigenous Language Use in Pakistani Rural Community", Global Social Sciences Review, VII (I), 264-278

-

TURABIAN : Tabassum, Samina, and Samina Amin Qadir. "Changing Trends in Indigenous Language Use in Pakistani Rural Community." Global Social Sciences Review VII, no. I (2022): 264-278. https://doi.org/10.31703/gssr.2022(VII-I).26